The Road to Financial Repression (2nd/Shorter Version)

How to allocate capital amidst a global regime change towards financial repression

(15 min read)

“The road to Hell is paved with good intentions”

— Proverb

Introduction

As the macroeconomic landscape of the last 25-years has been marked by deflation, inflation forecasters are now akin to “The Boy who cried Wolf”: they have been consistently wrong, so no one want to listen to them anymore. Yet, we now witness paw prints around the village (inflation rising), so for sheep’s sake it could be prudent to peek at the forest and see for ourselves.

First, let’s have a look at why the wolf never came despite the boy’s warning. For that, we will have to consider the economic and financial forces that have been driving disinflationary pressures over the past decades. This analysis will indicate that such forces are waning out, especially because the dynamics of both money creation and globalization are rapidly changing. Then, in the second part, we will lay out the arguments for persisting high levels of inflation (3 to 6% in OECD countries) and explain why Central Banks cannot raise rates. This will lead us to conclude, in the third part, that the only option left for governments will be to cap rates through financial repression. Lastly, in the fourth part, we will explain why we think this is a tremendous opportunity for Bitcoin.

SUMMARY

PART I: THE TIDE IS TURNING, FROM DISINFLATION TO INFLATION

1) In Search Of Lost Inflation

2) The Tide Is Turning, From Disinflation To Inflation

PART II: NAVIGATING FROM CHARYBDIS TO SCYLLA, THE INFLATION FLOOD AND THE REEFS OF INSOLVENCY

2) Why Central Bankers Won’t Raise Rates

PART III: CAPPING YIELDS THROUGH FINANCIAL REPRESSION & INFLATING THE DEBT AWAY

1) The Political Incentives For Slowly Redistributing Boomer’s Wealth

2) The Easy Way to redistribute Boomer’s Wealth

PART IV: FINANCIAL REPRESSION & THE ADOPTION OF A CENSORSHIP RESISTANCE ASSET (BITCOIN)

1) Banning Dinos And Regulating Exchanges

1) The Difference Between Bitcoin & Other Crypto: Censorship-Resistance

2) Bitcoin Adoption And Financial Repression

PART I: THE TIDE IS TURNING, FROM DISINFLATION TO INFLATION

1) In Search of Lost Inflation

Over the past 3 decades, money growth has been averaging 5-8% in OECD countries, central banks’ balance sheets have exploded, and deficit spending has been the norm rather than the exception. Therefore, many analysts, especially after the Great Financial Crisis and the implementation of QE, have called for the return of inflation. While over the period asset prices have consistently surged to higher levels, consumer goods inflation (CPI) was nowhere to be found.

The habitual counterargument being that CPI and PCE inflation metrics are totally rigged and thus unsuited as price level indicators. While there is definitely some truth to this, and despite us being very sympathetic to such view, we think there is more to this than flawed statistics.

First, we shall point out that much of the newly printed money has been used to increase production capacity, especially over the beginning of the current expansion.

After the Volker shock and at the time of the fall of the Iron Curtain, balance sheets were cleansed of debt. So, the late 80s and 90s witnessed large debt-financed capital expenditures, especially in the ex-communist world, supporting a shift towards offshore manufacturing in countries with low labor costs. Such a growth in manufacturing capacity combined with decreasing labor costs and decreasing financing costs put a huge downward pressure on consumer prices.

The second and very important factor is how we dealt with excess indebtedness and overinvestment.

Since LTCM blew-up in the wake of the Asian debt crisis, central banks have been worried about the implications of abrupt deleveraging episodes for financial stability. Hence, taking their role of lender of last resort very seriously, they have systematically cut rates and offered liquidity to distressed markets. Although this came from a good intention, it incentivized market participants to gear-up even more and postpone capital reallocations.

This whole situation where interest rates are lowered to avoid a debt-deflation had 2 major side-effects: i) maintaining excess production capacity, ii) lowering the discount rate, and thus incentivizing firms to compete for market share by lowering prices.

In essence, we printed a lot of money but the way we used it was very much disinflationary.

This, combined with a demographic boom and a technological revolution (the Internet) created the perfect disinflationary cocktail.

2) The tide is turning, from disinflation to inflation

So, we avoided inflation by:

· Lowering rates

· Favorable demographics

· Technology-driven cost alleviation

· Investing in manufacturing capacity in places where debt levels and labor costs were lower

The problem being that such a trend is unlikely to continue: rates hit the 0 bound (see chart below), demographics are slowing, information technologies produce decreasing returns and there is no new frontier in sight for large investments boom.

Furthermore, the COVID crisis revealed the western overreliance on China for manufacturing of essential goods, which combined with the already existing political pressures for industry re-onshoring have pushed the public to revise their opinions about the virtues of globalization. Therefore, political leaders in the West are pledging to repatriate strategic industries in their region of influence. This, associated with the escalating tensions between the US and China, as well as with the trend towards shortening supply chains (for ecological considerations, amongst other reasons), paint a general picture of deglobalization.

In such a context, COVID and the consecutive lockdowns acted as perfect catalyzers for inflation. The supply side disruptions induced by the closing of the economy combined with fiscal and monetary programs aimed at maintaining purchasing power formed the textbook “too much money chasing too few goods” situation and thus catapulted prices higher.

Indeed, as 2021 ends, inflation readings have picked-up across the board and currently stand at levels never seen in 40 years.

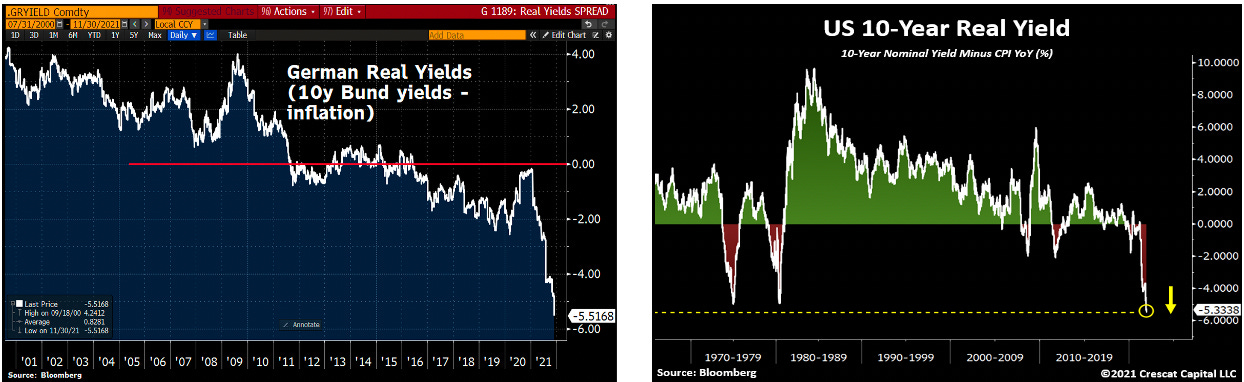

Bond yields, however, haven’t been allowed to rise at levels reflecting such inflationary pressure, and in consequence, most bonds now present with negative real yields.

So, it very much seems like all the above-mentioned disinflationary forces are vanishing. The ground is shifting behind our feet, and we are entering in a new economic landscape, more tilted toward inflation than deflation.

Yet, many analysts (if not the majority) are still convinced that inflation is transitory, or that Central Banks will react by raising rates and will thus bring inflationary pressure down, as signaled by J. Powell during the last Fed public address.

Let’s explain why we think none of this is likely.

PART II: NAVIGATING FROM CHARYBDIS TO SCYLLA, THE INFLATION FLOOD AND THE REEFS OF INSOLVENCY

1) Why inflation will persist

While we agree that part of the current inflationary pressures is induced by supply chain disruptions, which should resolve over the short to medium term (12 to 24 months), it is our view that much of the inflation is due to an acceleration in the growth of broad money (M2).

As illustrated by the chart below (M2 YoY % change), M2 growth rate has exploded to unprecedented levels. This is largely due to significant deficit monetization and to the Paycheck Protection Program enacted as a response to COVID-lockdowns, which incentivized banks’ lending through government guarantees on loan principals.

As financial news outlets focus disproportionately on Central Bank policy and CB’s balance sheet expansion, many market participants consider that Central Banks control the supply of money and would hence refute that the current situation is indeed novel. Such a stance is totally misguided as the Fed (and other OECD central banks for that matter) does not have the authority to create money.

When the Central Bank are engaged in QE, or other Open Market operations, they credit primary dealers with bank reserves, which are not legal tender (they don’t add to aggregate purchasing power). The rise in bank reserves leads to increased overall purchasing power only insofar as banks are willing to lend and/or governments to stimulate by deficit spending, otherwise reserves are trapped within the banking system and do not flow into the “real economy”. Since preceding QE rounds were neither accompanied by bank lending, nor by significant deficit spending, they never translated into significant CPI inflation.

So, what we want to monitor is the quantity of new money flowing into the economy and not the quantity of new reserves sitting idly on bank balance sheets. For that, we can turn to the variation of the difference of M2 and the size of the Central Bank’s balance sheet, corrected by fiscal expenditures (blue line). It gives us a better view of the variation of purchasing power, and hence of inflation (green line).

These monetary dynamics are central to the inflation-deflation debate, especially at a time when governments are committed to expanding the money supply, either by backing bank loans or by deficit monetization. Since the GFC, central banks have resorted to “unconventional measures” and governments often ran deficits, but those were rarely used in tandem. That changed after COVID. Indeed, over the last 2 years, we have witnessed a regime change in which politicians have trivialized printing money for political purposes. Many will argue that this was an exceptional measure motivated by the lockdowns, but betting on politicians relinquishing discretionary powers has empirically been a very bad wager.

As politicians and government bureaucrats have been desperate to create inflation over the past 12 years, we could well expect them to keep the magic wand in their pocket. Of course, the banalization of this politization of credit could only be enforced in OECD countries by invocation of emergency. Yet we have no shortage of those. The expedient employed through COVID could likely be used in the name of fighting climate change, closing the inequality gap, protecting consumer from inflation or strategic supply chain re-onshoring.

Furthermore, the discontinuation of the trends we mentioned in Part I, which played an important deflationary role, could add up to the inflationary pressures stemming from the acceleration in M2 growth.

Assuming our forecast is correct, this raises the question as to whether Central Bankers and politicians will allow long-term rates to reflect such level of sustained inflation.

2) Why Central Bankers won’t raise rates

During his last public speech, Federal Reserve Board Chair Powell signaled potential rates hike in 2022 (a maximum of 0.75%), as a response to mounting inflationary pressures. Yet, both public and private entities carry an enormous amount of debt, so a rise in rates could trigger an insolvency event, which is arguably the last thing public authorities want. There may be some room for rate hikes in the U.S. (maybe up to 1 to 1.5%) but it is less the case in other developed economies.

As the following tables illustrate (courtesy of the BIS), the ratio of total debt-to-GDP of non-financial entities, and more importantly the debt-service ratios of those entities stand at record levels:

Countries such as Belgium, Canada, China, Denmark, France, Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, and Turkey are arguably in no condition to withstand even the most moderate rate hikes.

So, as inflation readings are more elevated in the U.S., we forecast that the Fed will take the lead and try to raise rates in the first half of 2022, which will likely trigger a market sell-off in risk assets (reminiscent of the one that took place at the end of 2018), not least because many non-U.S. entities carry a heavy load of dollar-denominated debt and cannot easily turn to the FED for refinancing.

Another reason for our short-term bearishness in risk assets lies in the differential dynamics of money creation: to sustain a bubble, you need a continued or accelerating rate of growth in the money supply, and not just money supply growth. If the money supply continues its expansion, albeit at a slower rate, general prices must stabilize or decrease. Given the current money supply growth rate, there is little prospect for it to accelerate, or even stabilize.

But, since markets are very good at disciplining politicians, in the event of such sell-off, we expect the FED, pressured by Congress and the White House, to back-off from its tapering and to resume assets purchases. Amid a liquidity crunch and market plunge, few will hold a grudge against the FED for doing so, and Congress will be less divided on further deficit spending and/or additional government-backed credit creation. So, we are not denying that central banks will try to raise rates, we just think that the market will punish them for doing so, and that they will have to turn the ship around.

In essence, politicians and central bankers are trying to navigate from Charybdis to Scylla: if they cap rates at current level, signaling they will allow real rates to remain negative across the board, private investors will flee from bonds and central banks will be obliged to expand their balance sheets ad infinitum, which could very well be an unmitigated disaster for sovereign currencies; if, on the contrary, they let long-term rates rise in accordance with inflation, they will likely trigger an insolvency crisis.

For now, monetary and fiscal authorities in OECD countries are managing to keep the boat afloat, one liquidity crisis at a time, but as they find themselves stuck between a rock and a hard place, a more permanent solution will have to be considered. When the time comes, sooner rather than later, they will choose the path of least pain: capping long-term rates through financial repression.

PART III: CAPPING YIELDS THROUGH FINANCIAL REPRESSION & INFLATING THE DEBT AWAY

“The problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other’s people money”

— Margaret Thatcher

1) The political incentives for slowly redistributing boomer’s wealth

In the past, during periods when both debt loads and inflation have been elevated, after wars for instance, governments have been prone to cap bond yields at sub-inflation levels to inflate debts away. As the chart below shows, financial repression through negative long-term interest rates has been the norm rather than the exception in advanced economies over the 20th century.

Negative yields in real terms can be interpreted as a forced wealth transfer from savers to debtors. Therefore, implementation of such policy has often required very specific conditions to be met:

1) A preceding crisis during which politicians were given extended discretionary powers (war, pandemic, etc.)

2) A political justification for sizeable capital expenditures exiting the crisis (building back after the war, containing communism, fighting climate change, re-onshoring supply chains, etc.)

3) A shift in demographics and wealth gaps calling for wealth redistribution from one generation to the next.

Without 1), capital controls preventing flights from the domestic bond market cannot be enforced; without 2) the public has difficulty swallowing the pill of savings erosion and inflation runs too low for debts to be inflated away; and without 3), political leaders risk being voted out of office for implementing such wealth transfers.

The astute reader will have remarked that all those conditions are currently met:

· COVID has allowed politicians to seize the power to create money through government backed credits and deficits monetization. It is worth noting, that politicians are already using such expedient outside the scope of the COVID-emergency: the U.K. introduced a government backed mortgage program[1], France resorts heavily on the BPI[2] (a government backed bank) to funnel investment in “strategic sectors” and the European Union use the EIB to accelerate the transition to green energy sources[3].

· For arguably the first time in 50 years, there is bi-partisan consensus in the west for large capital expenditures: “greening industries”, infrastructure works, re-onshoring of strategic supply chains and critical production facilities, transformation of urban centers, etc.

· The skewed distribution of wealth between boomers and millennials, in a context of record asset prices (real estate, equities, fine arts, luxuries, bonds, etc.) preventing the latter group to hope for “a better life than their parents”, entails a strong political incentive for gradual wealth redistribution.

So, we should acknowledge that slowly redistributing boomers’ wealth to millennials through financial repression is not only feasible from a legal and political standpoint, but also profitable for the political entrepreneur. Lastly, if governments are to let inflation run high by refraining from raising rates, at some points, social bandages, such as vouchers, subsidies, government backed loans, and price controls, will be put in place. As history amply demonstrated over the past, such expedients will only add to the inflationary pressures and capital misallocations.

Yet, the subtle part of the argument here is not the “why”, but rather the “how”. Politicians always come up with new ways of spending money, but, more interesting to the investor, is how they find new ways to get it.

2) The easy way to redistribute boomer’s wealth

Capping yields solely through Central Bank’s balance sheet (“yield curve control”) would transfer the ability to determine the currency supply from public officials to speculators and is thus undesirable. Therefore, we expect governments to cap yields below inflation levels through regulatory means by passing laws that would force savings institutions to hold ever more government paper.

In effect, such measures are already in place in most OECD countries. Life insurances, pension funds, banks and many other similar institutions are legally obliged to have a certain ratio of government bonds on their balance sheets, especially in Europe. (As of this writing, French insurers & French banks hold 1/3 of French government bonds, while ECB holds 18%)

We believe savings institutions to be the perfect target for this because they are the diplodocus of the investment landscape: they are big, heavily regulated and lack agility. Besides, early redemptions from savings institutions are very difficult and come with heavy fiscal burdens, so capital flights are less likely than elsewhere. They are the low-hanging fruit for politicians in desperate needs of bond buyers.

In practice, this means that equities will continue to perform very well, as the discount rate will be fixed below the growth rate, and that bond attractiveness will fade (for the first time in 40 years). We expect this change to come very slowly, with politicians advancing step by step in forcing a larger range of regulated financial institutions to hold bonds. Equities should only suffer from this regime change if inflation start running too hot, or if such politicization of credit cause a forced deleveraging for firms unable to roll their debts on favorable terms (We will discuss this more in coming issues).

The tricky part of such maneuver, however, is not forcing savings institution to hold government paper, but rather preventing capital flight and controlling credit creation. As most politicians in emerging markets know, capital flight can cause runaway inflation through exchange rate depreciation and unconstrained credit creation can thwarts politicians’ effort to channel capital towards specific purposes. This is particularly important as the expected forms of financial repression will be implemented at the national level, not least because some countries will need them earlier than others (see part II).

Making a national financial system totally hermetic is practically unfeasible nowadays, but capital controls do not have to be perfect for the desired goals to achieved. Quite hermetic is often enough. New legislation can make it very difficult for most regulated financial institutions to export capital to foreign jurisdictions and/or to issue “undesired” credits. Indeed, the perspective of huge fines and/or jail sentences often suffice to discourage even the foolhardiest.

For this to work, there is, however, one unregulated financial channel that would need to be plugged: cryptocurrencies.

PART IV: FINANCIAL REPRESSION & THE ADOPTION OF A CENSORSHIP RESISTANCE ASSET (BITCOIN)

1) BANNING DINOs AND REGULATING EXCHANGES

Cryptocurrencies possess their own transaction settlement engines and can thus be used to make cross-border payments outside the purview of financial regulators. Hence, in a world of financial repression they would be the number one enemy.

Even though OECD countries are not yet at the point of implementing capital controls, a lot of forewarnings have been given to crypto enthusiasts. Over the last months, SEC Chairman Gary Gensler, and other regulators, have been very vocal about the fact that cryptocurrencies, and especially stablecoins, pose a threat to financial stability and must prepare for tighter regulatory oversight. Most of the thousands of cryptocurrencies circulating in our economies have been issued through Initial Coin Offerings, mimicries of IPOs conducted outside of any regulatory framework and solely relying on the native programmability of the underlying protocols for contract enforcement. Gensler, and his homologues in Europe, have made clear that those are in fact securities and would be regulated post-hoc in the coming years, if not months.

As those cryptocurrencies are Decentralized in Name Only (DINO) – to borrow the phrasing of Gensler, regulatory clamp-down is not only likely but also totally feasible. Most of the underlying projects have development teams, foundations, known founders and investors who would likely not ignore subpoenas.

Furthermore, most crypto trades and transfers are currently realized through centralized platforms called “exchanges”, operating within the regulatory framework of the jurisdiction they or their customers are located. As they are the bridge between the legacy financial system and the crypto world, closing them down, freezing their operations, or forcing them to apply controls on customers would most surely slow down, if not revert, cryptocurrency adoption.

Interestingly, China, which has a somewhat closed capital account, already banned onshore exchanges, and forced the exodus of most of its miners; Turkey, whose currency has been dangerously depreciating now imposes credit-seekers to pledge not to use borrowed money to buy Bitcoin or foreign currencies; and South Korea[4] just made a move against self-custody on non-KYC wallets, while other jurisdictions are warming-up to the idea.

2) THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN BITCOIN & OTHER CRYPTO: CENSORSHIP-RESISTANCE

While regulators can clamp-down on DINOs and submit exchanges to tighter regulations, they have no effective way to prevent people from using Bitcoin. Contrary to its copycats, Bitcoin is an acephalous, distributed and censorship-resistant network. No one can turn it off and it admits no physical point-of-failure that could be attacked, whether by regulators or any other attacker for that matter.

Regulatory takedowns of Bitcoin have already occurred in jurisdictions having some forms of capital controls in place (mostly emerging countries such as India, Nigeria, China, Turkey, etc.), but were short-lived as they often failed to eradicate use. Indeed, insofar as the user self-custodies his coins outside exchanges, there is no stopping him from peer-to-peer exchanging bitcoin, nor preventing detention.

At the fundamental level, interacting with Bitcoin is multiplying numbers and exchanging encrypted messages over telecommunication channels, so little can be done to “ban” Bitcoin apart from outlawing math, speech, or the Internet altogether.

That is not to say that further regulating exchanges will bear no effect on the adoption or the price of bitcoin. In the sort-term it will indeed put huge downward pressure on the price of the orange coin. However, past experiences have amply demonstrated that it can only curb adoption momentarily. The harsher the financial repression, the sexier the exit from it; so, as governments cannot effectively prevent people from using Bitcoin, by “banning” it, they often accidentally advertise for it.

The empirical demonstration of their impotence in this matter often tends to convince otherwise skeptical people that Bitcoin indeed is the exit. In a sense, financial repression is an environment in which Bitcoin strives because it perfectly outlines its most important (and often overlooked) value proposition: censorship-resistance.

3) BITCOIN ADOPTION AND FINANCIAL REPRESSION

Much ink has been spilled over the virtues of bitcoin as a store of value, conferred by the immutability of its monetary policy. While this is correct, it also misses the crucial innovation in Bitcoin: the fusion of information and property.

Many assets act as good store of value (real estate, blue chip stocks, precious metals, fine art, wines, etc.) but none are totally censorship-resistant: your estate cannot travel thousands of miles in milliseconds, your stocks are yours until your broker (or its regulator) says otherwise, your precious metals are costly to transport and easy to seize and your Giffen goods won’t do if you have to rely on the black market.

As Bitcoin is pure information, when it is correctly used, it is impossible to seize, impossible to censor, as well as easy and cheap to verify. Currently, most people in advanced economies don’t know how to use it. They deposit it on exchanges and sell when they are in profits. They view it as a speculative asset, nothing more, because they have no use for censorship-resistance.

In financially repressed countries, behaviors are quite different. As the infographic below shows, Bitcoin’s adoption is most advanced in financially repressed countries (only notable exception is the US).

(The index measures On-chain value received, weighted by purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita, and hence seeks to determine how significant total cryptocurrency activity volume in a country is compared to its wealth per resident)

As Charlie Munger puts it: “show me incentives, I will show you outcomes”. With financial repression intensifying over the coming years, incentives will shift from crypto to bitcoin and from depositing on exchanges to self-custody, as will the outcomes.

Forecasting regulatory clamp-down on cryptocurrencies while at the same time advocating for Bitcoin ownership can seem paradoxical. Yet, it is a misconception that stems from a poor understanding of what Bitcoin is for. Bitcoin strives the most in areas and at times of financial repression because it has been designed as a censorship-resistant asset (see chart below).

As our financial environment becomes ever more resemblant of that of Argentina, your financial behavior will become ever more Argentinian-like and that is very good for Bitcoin’s adoption.

Conclusion

Over the last 40 years, we printed a lot of money but used it in somewhat productive ways, so it didn’t cause too much CPI inflation. Yet, as we have used monetary policy to prevent any system wide deleveraging, we accumulated an unprecedented amount of debt which now profoundly constrain the ability of monetary authorities to fight inflation. On top of this, manipulation of interest rates has favored malinvestment and has thus diminished our ability to service all this debt by genuine growth. If the past holds any lesson, it is that such indebtedness can only be cope with a long period of sustained inflation and negative real yields.

In theory, there should be a relationship between inflation and long-term rates, but we are not in a theoretical world. In the real world, rates cannot be allowed to rise to levels that would bankrupt everyone including governments. So, we are approaching decision time: either the state will have to go on a diet and private entities default en masse, or bureaucrats and politicians will engineer a period of negative interest rates to inflate debts away. Our guess is that textbook economics and boomer wealth preservation matter less to the political entrepreneur than his reelection.

If we are right, this means that the investment landscape will gradually become very different from what it has been over the past 40 years. At first, it will feel good as equities, real estate and other hard assets skyrocket in value (you are here). Then will come restrictions on financial freedom, and it will feel less good. When that time comes, it will not be bonds, nor real estate in London, nor growth stocks, nor crypto that will shield your portfolio, but Bitcoin. As Bitcoin is a truly censorship-resistant asset (when it is correctly used) it will weasel its way out of any cage governments will built for it. Consequently, in a financially repressed world Bitcoin will command a high (and maybe extremely high) monetary premium.

This is the first edition of a monthly Newsletter dedicated to macroanalysis for the 2020 decade. Following Newsletters will be available on substack and will delve in more depth into this core thesis of Financial Repression. Many other investment opportunities, pertaining or not, to Bitcoin will be discussed in coming editions.

Disclaimer

This Newsletter should not be considered as financial advice. Its content is for educational purposes only. Readers should do their own research.

We are doing our best to prepare the content of this site. However, Institut Bitcoin cannot warranty the expressions and suggestions of the contents, as well as its accuracy. In addition, to the extent permitted by the law, Institut Bitcoin shall not be responsible for any losses and/or damages due to the usage of the information on our website.

By using our website or downloading this newsletter, you hereby consent to our disclaimer and agree to its terms.

The links contained on our website may lead to external sites, which are provided for convenience only. Any information or statements that appeared in these sites are not sponsored, endorsed, or otherwise approved by Institut Bitcoin. For these external sites, Institut Bitcoin cannot be held liable for the availability of, or the content located on or through it. Plus, any losses or damages occurred from using these contents or the internet generally.

[1]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/965665/210301_Budget_Supplementary_Doc_-_mortgage_guarantee_scheme.pdf

[2] https://presse.bpifrance.fr/bilan-dactivite-2020-et-perspectives-2021-de-bpifrance/

[3] https://www.climatechangenews.com/2020/11/12/eib-approves-e1-trillion-green-investment-plan-become-climate-bank/

[4] https://www.theblockcrypto.com/post/128735/korea-crypto-exchange-%e2%80%8ecoinone-withdrawals-external-wallets